I’ve been reading a lot recently – let’s face it, apart from watching TV and working out on the basement exercise machines, there isn’t much else to do during the coronavirus lockdown. And one of the things I’ve been reading a lot about is the Constitutional Democratic (or Kadet) Party, which was Russia’s leading liberal political organization in the early years of the twentieth century. The Kadets have long since been consigned to Trotsky’s infamous dustbin of history, but my reading has turned out to be surprisingly relevant to the book I’m reviewing today – Joshua Yaffe’s Between Two Fires. It’s all a matter of political compromise.

The thing you have to grasp about the Kadets is that they were often rather dogmatic. As one Russian historian puts it, ‘The Russian liberal of the early twentieth century wasn’t able to abandon the role of idealistic oppositionist and recognize realities and the necessity of compromise’. Looking back on events, one Kadet, Prince V.A. Obolenskii, summed up the prevailing attitude in this way:

We thought the following: the authorities were hostile to the people. Thus, any official in state service, however useful, was in the final analysis harming the people as he was strengthening the power of the government. Besides which, we saw before us a whole series of people of very left wing convictions who had entered government service and gradually got accustomed to compromise and lost their oppositional zeal.

Between 1905 and 1917, the refusal to compromise with the Russian state had catastrophic consequences. On various occasions in 1905 and 1906, the Kadets were offered a role in government under first Sergei Witte and then Pyotr Stolypin, but always refused the offer, preferring instead to seek the complete destruction of the autocracy. Likewise, instead of using Russia’s new parliament, created in 1905, to propose constructive reform measures, they chose instead to block Stolypin’s reform program and use the parliament as a soap box for denouncing the government. Eventually, in 1917 they got their wish and saw the hated autocracy destroyed. But it didn’t do them any good, as they themselves were swept away by the tide of revolution just a few months later.

The more sensible of the Kadets understood that they were making a huge mistake, that compromising with the state, however much you dislike it, is often a much better option than seeking its overthrow. As shown in another book I’ve just finished reading – a biography of the prominent Kadet jurist and politician Vasily Maklakov – Maklakov repeatedly urged his colleagues to understand that democracy would never be possible in Russia unless people learned the art of compromise. But his fellow Kadets paid no attention. They paid for it dearly.

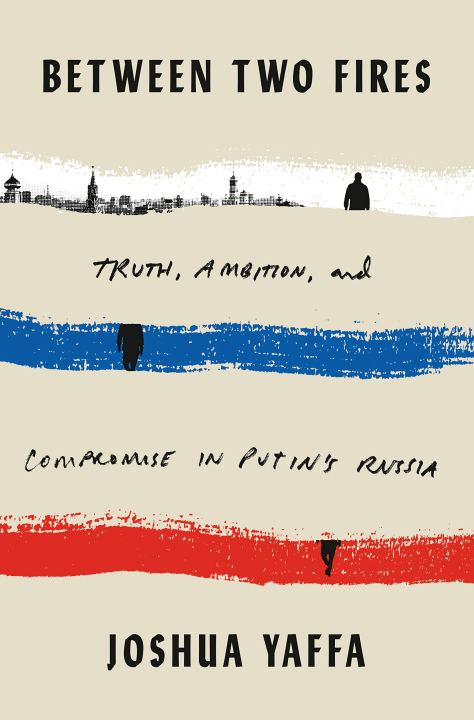

The lesson of all this is pretty clear, but reading Yaffa’s Between Two Fires, it seems that there are some who would prefer that Russians again adopted the principles of the Kadets. For the theme of the book is the moral dangers of compromising with the Russian state (thus the subtitle ‘Truth, Ambition, and Compromise in Putin’s Russia’), and while Yaffa states that he doesn’t condemn those who choose to cooperate with the ‘Putin regime’, it’s pretty obvious that he thinks that it’s not a good thing.

Yaffa, a journalist with The New Yorker, starts his book with a discussion of Russian sociologist Iury Levada and his concepts of Homo Sovieticus and the ‘wily man’. The Soviet system, Levada argued, created people who learned to adapt to the authoritarian state and ‘to swim with the current rather than against it’, in order to extract as much benefit as they could for themselves. The same phenomenon, Yaffa argues, is what characterizes Putin’s Russia – people who believe that ‘the best, if not the only, way to realize their vision [is] in concord with the state’. While this choice serves them as individuals, it results in the perpetuation of the authoritarian system, which in the end harms everybody.

As I’ve mentioned on this blog before, Levada’s ideas about the ‘Soviet man’ are hotly contested and are considered by some sociologists to be rather misleading. They are maybe not the soundest basis for an analysis of modern Russia (not least because they imply that the Soviet Union and modern Russia are not very different). Despite this, Yaffa runs with the Levada stereotype, and for the rest of his book provides a series of case studies of people who he thinks exemplify this model of the ‘wily man’ (or woman).

In this way, his book takes the usual form of journalistic endeavours, that is to say a series of anecdotes and personal stories which are meant to somehow personify the larger whole. As these endeavours go, Between Two Fires is rather well written. The stories are engaging, the characters compelling, the style of writing pleasing. But as an academic I feel that it suffers from the same problem as all such journalistic works, which is that anecdotes and personal stories don’t really do any more than tell you about the specific people being described. Methodologically speaking, using them to make broader claims about a country is somewhat dodgy. This is particularly true when the people concerned are far from typical, as Yaffa’s are: the head of Channel One TV; a prominent Chechen human rights activist; a rebellious priest; a Crimean zoo owner; a famous doctor; and an equally famous theatre director. These aren’t ordinary Russians.

Take, for instance, the Crimean zookeeper, Oleg Zubkov. After having played a prominent role in the events which led to Crimea’s reunification with Russia, Zubkov fell out with the local authorities, in large part, it seems, because he has a low tolerance for rules and procedure, and so didn’t like the fact that once the Russians started running the show, he couldn’t operate any more with the freedom he had under the laxer rule of the Ukrainians. The result was a series of conflicts with Russian officialdom, which led him eventually to regret his decision to support Crimea’s secession from Ukraine.

Zubkov’s is an interesting story, and Yaffa tells it well. But his disillusionment is not the norm. In fact, opinion polls show that an enormous majority of Crimeans continue to support their province’s annexation by Russia, and believe that their lives have improved because of it. In effect, what Yaffa has done is take what might be the least typical Crimean he could possibly find and then portray him as being somehow enlightening about the Russian population as a whole. As I said, methodologically speaking, it’s more than a little unsound.

The other thing which strikes one about Zubkov is that he’s about as far from being a ‘wily man’ as one could imagine. Yaffa actually admits this, saying that ‘he didn’t fit the particular contours of wiliness a la Russe.’ And the thing is, he’s not the only one in this book. As far I could tell, only one of the case studies – Chechen human rights activist Heda Saratova – properly fits the model of someone compromising their morals for apparent self-gain. Other people studied – like Zubkov, priest Pavel Adelgeim, and theatre director Kirill Serebrennikov – come across as downright confrontational in their approach to the authorities. Serebrennikov’s only ‘compromise’, if you can call it that, was to accept state money to fund his plays. And what did he do with it? Stage events abusing the state! It’s hard to see why this is ‘wily’.

Other cases in the book, such as Channel One head Konstantin Ernst and doctor Elizaveta Glinka, display a similar lack of ‘wiliness’, in that they seem to have genuinely believed in what they were doing. Cooperating with the state wasn’t, therefore, any sort of ‘compromise’. In short, having set up the construct of the ‘wily man’, Yaffa doesn’t, in my opinion, provide very good examples of it.

What we do see, though, are various examples of what I might term ‘Kadetism’ – that is to say, dogmatic rejection of any cooperation with the Russian state, no matter how beneficial it might appear to be, on the grounds that it somehow legitimizes authoritarianism and so aids in the ultimate oppression of all. This comes out in critical remarks about the main protagonists made by various side characters, most of whom are of what one might call a ‘liberal’ persuasion.

This is most obvious in the chapter about Elizaveta Glinka, a doctor who won fame providing aid to the homeless in Moscow before going to war-torn Donbass to extract people suffering from the shelling, and then tragically dying in an air crash while en route to Syria. Glinka’s aid to the people of Donbass comes in for considerable criticism, because she enlisted the help of the Russian government and refused to criticize the Kremlin for its role in the war. According to some, she thereby legitimized Russian ‘aggression’ in Ukraine. As one critic cited by Yaffa complained to Glinka: ‘With your reputation, you give these people a kind of indulgence – that is, the opportunity to continue to sin.’

‘Do you think it would be better if the children I brought out had died?’ said Glinka in response, to which the answer of some of her opponents seems to be yes. Without ever saying as much, Yaffa kind of agrees. He writes of ‘Glinka’s wilful blindness to the Kremlin’s culpability in Ukraine’, and remarks that ‘Neutrality is itself a position: refusing to apportion blame for violence means letting one side or the other off the hook.’ By describing the conflict in Ukraine as a ‘civil war’, Glinka ‘came to match, quietly and subtly, Moscow’s preferred version of events,’ Yaffa says. By helping the victims of war, she legitimized the violence which made them victims. In other words, by helping people, she made them suffer. The logic is rather like of communists who used to complain that, ‘Subjectively you may be a liberal, but objectively you’re a fascist’.

I found this odd. First, neutrality is the norm for those providing aid in war zones. Nobody asks the International Committee of the Red Cross which side it is on, and it never says; its capacity to give aid depends on neutrality. Second, the war in Ukraine is more complex than just Russian aggression. Yaffa’s not stupid. He must know who it was who was shelling the places Glinka was visiting to extract those in need, places like Slavyansk, Kramatorsk, and Donetsk. And he must know that it wasn’t the Russian army. But he never tells you this. It’s more than a little disingenuous.

For Glinka’s critics, any sort of cooperation with the Russian state is suspect, because ultimately everything is political, and the higher political struggle should take preference over real and concrete achievements in the here and now. To me, perhaps the key passage in Between Two Fires recounts a discussion Yaffa had with the chairman of the Kremlin’s human rights council, Mikhail Fedotov, concerning protests about garbage dumps, and whether it was better to fire the local governor or take concrete action to fix the problem:

‘I don’t care who the governor is – what’s important to me is that the garbage dumps are destroyed,’ he [Fedotov] said. That sounded sensible, but it overlooked the fact that in today’s Russia, a massive garbage dump doesn’t operate in violation of the law without ties to local power brokers, politicians, and bureaucrats. You could play Whac-a-Mole with garbage dumps to eternity, but at a certain point, the problem becomes unavoidably, well, political.

In short, forget concrete progress, ‘overthrow the regime’! In a famous 1909 collection of essays entitled Vekhi, the philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev complained, ‘The intelligentsia’s basic moral outlook can be summarized by the formula, “May the truth perish if its death will give the people a better life … down with the truth if it stands in the way of the cherished call ‘Down with autocracy’”.’ It’s much the same mentality. We must hope and pray that it doesn’t produce the same tragic consequences.

Sorry, but I don’t understand anything. What exactly was the political ideology of the Kadets? Bourgeois Constitutionalist? something like that?

LikeLike

The Kadets demanded a constitutional, rule-of-law state (pravovoe gosudarstvo), which was to be achieved by summoning a Constitutional Assembly elected by ‘four-tail’ suffrage – universal, direct, equal, and secret (something which, of course, at that time didn’t exist anywhere in the world).

On the agrarian issue, they called for redistribution of land to the peasants by means of forcible expropriation of land from large landowners, with compensation at less than market value. The land wouldn’t be the peasants’ property, but placed in a state land fund, from which it would be distributed as appropriate. This contrasted with Stolypin’s proposal which avoided expropriation, but instead allowed peasants to consolidate their allotments and turn them into their private property.

Some historians consider Stolypin’s position more obviously ‘liberal’, due to the property element, and the Kadets therefore as not liberal but radical.

Kadets viewed their main task as ending autocracy. This led to the slogan ‘no enemies on the left’. While disapproving of revolutionary violence, they therefore tended to turn a blind eye to it.

On the nationalities question, they believed in cultural, but not political, autonomy. Federalism was opposed, as it could lead to national secession. Instead, the idea was decentralization to the provinces, so Ukraine for instance would have several provinces, each of which would enjoy a degree of autonomy, have the right to use Ukrainian language etc, but there would be no ‘Ukraine’ as such. At least that was the majority position. There was also a minority of great Russian nationalists, who wanted Russification (notably Peter Struve).

On foreign affairs, they were defeatists in the Russo-Japanese War, but turned into rabid imperialists in WW1, demanding the conquest of Constantinople etc.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the explanation, Professor. Sounds like the Kadets had a decent platform, but fell into the WWI trap. That war was the maw that gobbled up and chewed up everybody’s platform, including most of the Socialist Second Internationale. If the Kadets had had a proper Defeatist position like they did with the Japan war, maybe they could have come out on top.

To this day, I cannot fathom how any self-respecting Russian political party of the time could have supported the Romanov alliance with England/France. It just doesn’t make sense to me!

LikeLike

Predictably, Professor, you are making KaDets (also “Party of the People’s Freedom/Партия Народной Свободы” aka ПарНаС) look better than they were in reality, so that people, who have no idea about them might start feeling a bit of sympathy. Well, given the fact that these liberals of the past, indeed, got themselves into the Dustbin of History, who else, but the modern liberals to eulogize them?

1) On the peasant/land question. First of all, KaDets didn’t plan of distributing ALL of pomeshiks’ (that’s it – legally privileged noble landowners) land – only vaguely termed “partial”. Also absent in their programme any promise to compensate for that land “below it’s value” – the term used in their October 1905 Party Programme is “fair compensation”, which could’ve come either from the State or from the peasants.

Also, one cannot mention the land question out of the general picture of their economic program, which presumed a wide-ranging (and unregulated) privatization of the state property. Therefore, noble lands were not seen as primarily, let alone the only source of “beefing up” landless and small-owner peasants – KaDets primarily counted on allocation (for “fair compensation”, right) of the state, crown, ministerial and monastery lands, before they’d have to cut the “sacred cow” of the pomeshik landholdings. Left unsaid, of course, is just what number of peasants would ever allow themselves to pay even “fair” compensation for this land.

TL;DR – they wanted to “curb” the power base of those, they deemed to be the “pillars of autocracy”, and (because they liked to blindly cospaly Anglo-Saxon legislation and way of life) to empower kulaks (“enterprising farmers”). All in all, their answers to the “land question” were half-arsed given Russian Empire’s reality. In 1st Duma they failed to reach the agreement with “Trudoviks”, because the latter even then insisted on nationalization of all pomeshik lands.

2) On the national question. KaDets, we are told repeatedly, were Smart People ™, consisting of the “brain” (actually – not) of nation. They surely numbered among their ranks enough lawyers and law professors. Thus, they had to understand that by fighting precisely against Russian monarchy, they were opening the entire warehouse full of nationalism cans of worms. E.g. – Finland was in direct unia with the ruling dynasty of Russia. No dynasty – no Finland. Same goes for Poland, but by 1917 it was a moot point, given German occupation of that territory. And yet KaDets insisted on “united and indivisible Russia” with the offers of (limited) autonomy.

[Most eloquently about their moral consistency speaks the fact, that Pavel Milyukov ended up in 1918 in the German controlled Ukrainian Hetmanate, all loud words about the Ukraine as a country and “War Till Victory” forgotten]

From one Duma to another KaDet “reiting” kept sliding down because of their aforementioned half-arsed approach to… everything. Per V.I. Lenin’s description of their activity in the 2nd Duma: “No longer do they experience last year’s hesitation between reaction and the people’s struggle. There is a direct hatred of the popular struggle, a direct, cynically proclaimed desire to end the revolution.” (Complete Works of V.I. Lenin, 5th ed, v. 15,p.20).

After 3rd of July counter-revolution in 1907 KaDets felt themselves extremely “compromising” with the “Regime”, thus undermining the central premise of your blogpost, Professor (see the results of their 5th party congress). In the summer of 1909 Pavel Milyukov while attending the official diner of London’s Lord-Mayor (imagine that!) endeared himself for his poshy-posh hosts by proclaiming, that “As long as there is a legislative chamber in Russia that controls the budget, the Russian opposition remains the opposition of his majesty, and not his majesty”. In November 1909 KaDet party conference voted to make it the official policy.

And then after February 1917 they become the Power. They proceeded to fuck up. Yes – they, for members of that party remained in the Provisional Government till the end. All old promises – forgotten (“delayed”). Unsurprisingly, by late summer 1917, forgetting lofty liberal ideology espoused in their party programme of yore, they began seeking convergence with the “healthy elements” of monarchists, financial and industrial capitalists plus dissatisfied officers, in order to establish a dictatorship, i.e. they began planning counter-revolution. In other time and in other country, they could have been accused of enabling fascism, if not Nazism – but our dear modern day liberals both inside and outside Russia, would, surely, dispute such claim with a foam in their mouth, while denouncing “bydlo” and “deplorables” all around them 🙂

[Kornilov’s revolt with its support and preparation by the KaDets was not a “fluke” – their 10th party congress of 14-16 (27-29) October 1917 officially enshrined in their programme to have another attempt to establish a truly right-wing dictatorship]

LikeLike

This was brilliant. Particularly liked the apt quote from Berdiaev.

LikeLike

My copy of Huxley’s ‘Brave New World’ starts with a quote from Berdiaev. Its a quote that would have been apt for ‘1984’. Would like to know more about him.

LikeLike

“…[W]hile Yaffa states that he doesn’t condemn those who choose to cooperate with the ‘Putin regime’, it’s pretty obvious that he thinks that it’s not a good thing.

“Yaffa, a journalist with The New Yorker, starts his book with a discussion of Russian sociologist Iury Levada and his concepts of Homo Sovieticus and the ‘wily man’…The same phenomenon, Yaffa argues, is what characterizes Putin’s Russia – people who believe that ‘the best, if not the only, way to realize their vision [is] in concord with the state’. While this choice serves them as individuals, it results in the perpetuation of the authoritarian system, which in the end harms everybody.

“[H]is book takes the usual form of journalistic endeavours, that is to say a series of anecdotes and personal stories which are meant to somehow personify the larger whole.”

TL;DR – “Between Two Fires – Chutzpah and Gewalt”.

“In fact, opinion polls show that an enormous majority of Crimeans continue to support their province’s annexation by Russia”

No idea what “annexation” you are talking about here, Professor. It was a reunification – a term you used in the paragraph above.

“In effect, what Yaffa has done is take what might be the least typical Crimean he could possibly find and then portray him as being somehow enlightening about the Russian population as a whole. As I said, methodologically speaking, it’s more than a little unsound.”

No, but that’s a typical MO of the Western pundits, pressitudes and think-tankers – find some “Russians”, that would be more sympathetic to the Western middle-calls public, and then work their “sympathetic magic(k)”. The point is not to tell the truth, the point is to peddle a story (“a narrative”) to the people with monies.

“Other people studied – like Zubkov, priest Pavel Adelgeim, and theatre director Kirill Serebrennikov… Serebrennikov’s only ‘compromise’, if you can call it that, was to accept state money to fund his plays. And what did he do with it? Stage events abusing the state! It’s hard to see why this is ‘wily’.”

Stealing money is rather “wily” act. As for this “priest” – ain’t he the one who’s from the pro-LGBTQIWORDSALAD+ crowd?

“In short, having set up the construct of the ‘wily man’, Yaffa doesn’t, in my opinion, provide very good examples of it.”

When a Jew like Yaffa tries to peddle the narrative that the whole of the Russian people are “wily”… that’s the ultimate form of the anti-Semitism.

“The logic is rather like of communists who used to complain that, ‘Subjectively you may be a liberal, but objectively you’re a fascist’.”

One – that unnamed (by you) communists were 100% right, if one only look at the modern liberals. Two – hope you are paid extra for inserting anti-communist drivels in every single of your posts, otherwise you are sinning against the Holy Capitalism for doing such thing for free and, thus, helping and abetting the communism, Professor.

“In a famous 1909 collection of essays entitled Vekhi, the philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev complained…”

Key word – “complained”, but never offered a working solution. All of “Vekhi” amounts to the wailing and gnashing of teeth, and admittance of one’s pathetic impotency.

LikeLike

Regarding a comment above, Russia’s WW I alliance took into consideration Serbia and was therefore not exclusively geared towards Britain and France.

Interesting read:

https://www.abebooks.com/book-search/title/political-memoirs-1905-1917/author/paul-miliukov/

LikeLike

Re Yaffa’s reasoning about the children of Donbass, it sounds familiar

LikeLike

I’ve been reading a lot recently – let’s face it, apart from watching TV and working out on the basement exercise machines, there isn’t much else to do during the coronavirus lockdown.

Good to hear, silver linings and all that.

Otherwise:

Master of Ceremony

changed from the New Yorker’s Dec. edition? Titles (ex-post updated version to print? Or post-ante?). …

from:

Channeling Putin

to

The Kremlin’s Creative Director

Admittedly I love portraits both in the arts no matter if in image or in words.

Otherwise, it feels that Michael Kimmage in/on Foreign Policy may be to an even more hidden extend a meeting of one soul ‘in bodies twain’: The Wily Country, Understanding Putin’s Russia, Michael Kimmage March/April 2020

https://www.americanacademy.de/person/joshua-yaffa/

LikeLike