I’ve just finished doing the index for my book on Russian conservatism, and in the process I noticed that I had mentioned some names and terms much more often than I thought I had. Peter the Great, for instance, is the second most mentioned person in the book (Nicholas I is the most), and that’s odd because I don’t discuss him or his reign at all. In fact the book starts in the early 1800s, about 100 years after Peter. But it seems that the shadow he cast had such a powerful effect on nineteenth century Russian conservatives (who to a large degree were reacting against the process of Westernization that Peter set in motion) that his name kept cropping up regardless.

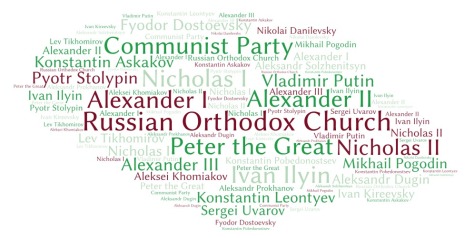

That got me thinking. It turns out that the index provides quite a useful tool in determining what persons and subjects my book addresses, and thus determining who and what are really important. So, with that thought in mind, I set about quantifying Russian conservatism by totalling the number of mentions people and ideas get in the book, and then producing some word clouds. The results provide a visual rendition of Russian conservatism past and present.

The first world cloud shows the persons and institutions which were most often mentioned in the book. The first thing which strikes one is the centrality of the Russian Orthodox Church. Beyond that, though, this word cloud is perhaps rather misleading as the most prominent names aren’t those of conservative philosophers but of Russian tsars, e.g. Peter the Great, Nicholas I, Alexander I, I, and III, and of the Communist Party and Vladimir Putin. In short, the dominant figures are Russia’s rulers. Yet, except for Nicholas I and Putin, I say very little about any of them. They get a lot of mentions, but they’re mostly in passing, as a way of providing context.

But that itself reveals something. An ideology like liberalism can be seen as abstract and absolute, that is to say that it embodies certain absolute, abstract ideas which are considered valid regardless of time and place. Conservatism by contrast is relative; it is what is called a ‘positional’ or ‘situational’ ideology – i.e. it depends on the given situation. Another way of looking at it is as a ‘reactive’ ideology – i.e. it’s a reaction to whatever is happening in the time in question. In short, with conservatism, context matters.

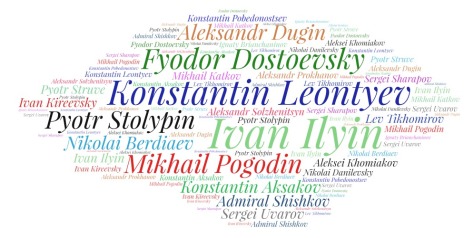

For word cloud number 2, I deleted all of Russia’s rulers, as well as institutions such as the Church and Communist Party. What was left was the names of the political philosophers and politicians who have had the most impact on the development of Russian conservatism. This is what I got:

The word cloud exaggerates very minor differences. Also, this isn’t an objective measure; it just represents who I chose to put in the book. Somebody else might have put in more Danilevsky, let Ilyin, more Panarin, less Dugin, or whatever. But I suspect that whoever did it, the result wouldn’t be too far different. The same gallery of individuals would appear, starting with Shishkov and Karamzin, going through the Slavophiles, the post-Slavophiles (Dostoevsky, Danilevsky, Leontyev etc), the likes of Tikhomirov and Sharapov, and then through the emigration, the later Soviet period, and onto today. The important thing to note is that there isn’t any single figure who stands out as the core person in Russian conservative thought.

The same can be said of the post-Soviet period. This word cloud includes only references from the part of my book dealing with events post-1991:

A number of women make an appearance in this word cloud, Nataliia Narochnitskaia being an example. Russian conservatism remains male-dominated, however.

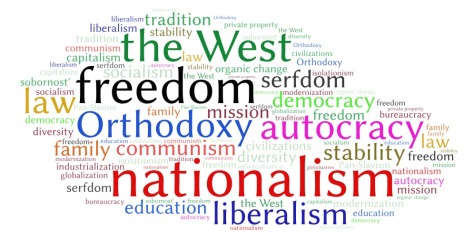

Instead of people, the next two word clouds show keywords which occur in the book. They illustrate the issues with which conservatives have been concerned, either because they have promoted them (autocracy, Orthodoxy, nationalism, family, stability, etc), or because they’ve been reacting against them (the West, liberalism, etc). The first word cloud covers the entire period from 1800 to today:

I find that in this word cloud I have reproduced Sergei Uvarov’s definition of Official Nationality: ‘Orthodoxy, Autocracy, Nationality’. It seems that those three things really are the primary concerns of Russian conservatism. That said, there are some surprises here. The most notable is the dominance of the theme of ‘freedom’. This is not something I had expected when starting my research, and yet my studies showed that, despite their support for authoritarian forms of government, Russian conservatives have indeed been very concerned with promoting freedom. This is in part due to the censorship they suffered under both the Imperial and Soviet regimes, which has produced a long-standing interest in freedom of speech. Freedom, though, is often interpreted in a way different from the Western liberal understanding, in terms of what is called ‘inner freedom’. Still, its prominence in this word cloud is striking. Also surprising to me was the importance of education. To many conservatives, the core objective is moral improvement. Education has therefore been considered a matter of great importance.

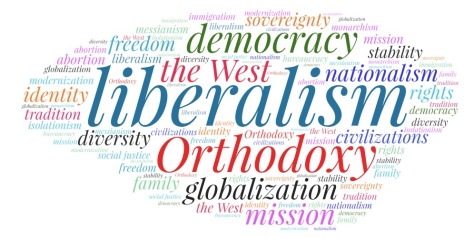

Post-Soviet concerns somewhat differ, as shown by this word cloud which references only terms used in the part of my book post-1991:

Orthodoxy remains, but autocracy has entirely dropped out of the cloud, to be replaced with discussions of democracy and liberalism. Also important are matters concerning Russia’s relationship with the West, as seen by the prominence of words like ‘the West’, ‘globalization’, ‘sovereignty’, ‘mission’ (i.e. Russia’s mission in the world) and ‘civilizations’. If this word cloud is anything to go by, contemporary Russian conservatism is a combination of Orthodoxy and a reaction to Western liberalism and globalism, which together have created a sense of Russia as a distinct civilization with a global mission (associated with another word on the cloud – diversity). All in all, I think, that’s not a bad definition.

“That got me thinking. It turns out that the index provides quite a useful tool in determining what persons and subjects my book addresses, and thus determining who and what are really important… The first world cloud shows the persons and institutions which were most often mentioned in the book. The first thing which strikes one is the centrality of the Russian Orthodox Church… Beyond that, though, this word cloud is perhaps rather misleading as the most prominent names aren’t those of conservative philosophers but of Russian tsars… They get a lot of mentions, but they’re mostly in passing, as a way of providing context.”

Several times I was about to write, professor, that you’re criminally neglecting the question of the Russian monarchism while trying to describe the conservatism of the period. After all – this is your book. So far, I limited myself to namedropping Pobedonostsev, but, really, I don’t think that you ever discussed him (and his views and their impact) at any lengths.

Now, it seems you’ve finally noticed a certain… issue. Another issue would be shoehorning (if you choose so) all the “non-mentionables” in the, ah, comely and coherent fashion. How one can mention Karamzin, Uvarov and Dostoyevsky, but totally “forget” Pobedonostsev (and other, less handshakable figures from the reign of Nicholas II) is also… interesting.

Another quibble is purely linguistic. Correct me if I’m wrong, but could it be possible that there is such an abundance of the word “nationalism” in you book, because you chose it to translate the term “народность”? Because this would be wrong. Uvarov’s “Народность” =/= “Nationalism”. The latter meant the political nation as pertaining to the full fledged capitalist nation. Brandishing scary term “nationalism” left and right when dealing with Russia is such mauvais ton, yet so popular among the mainstream of the West’s media and Academia.

The same goes to the word “freedom”, for which there are 2 possible variants in Russian – either “воля” or “свобода”. The differences between the two are important. Do you draw this distinction in your work? You wrote:

“Freedom, though, is often interpreted in a way different from the Western liberal understanding, in terms of what is called ‘inner freedom’”

so I’m not so sure about your understanding of the nuance.

LikeLike

Monarchism gets some mentions, but isn’t an important attribute of Russian conservatism until the revolution, Prior to that, the focus is on ‘autocracy’ – ie a certain form of monarchy. But even after the revolution, monarchism is subdued. As I explain in my book, among emigres, the ruling doctrine was the Whites’ idea of non-predetermination. Much the same is true today. Self-proclaimed monarchists are few and far between. There are those who have obvious sympathy for monarchy, but they avoid the subject generally, and instead follow a line somewhat similar to non-predetermination. This is true of the Orthodox Church, some of whose representatives say that they like the idea of monarchy, but who then generally go on to say that it isn’t the Church’s job to decide the matter.

Pobedonostsev is there. See top of second word cloud. As I said, the word cloud software exaggerates small differences.Pobedonostsev gets quite a reasonable amount of attention in the book.

The third part of Uvarov’s triad is normally translated into English as ‘nationality’, rather than nationalism. My index actually has a number of subsections of nationalism – popular nationalism, Romantic nationalism, dynastic nationalism, ethnic nationalism, etc. But for these word clouds, I threw them all together.

Re. freedom, generally speaking we’re speaking svoboda – e.g. svobodnoe slovo,

LikeLike

“Monarchism gets some mentions, but isn’t an important attribute of Russian conservatism until the revolution”

Which one? 😉

“Prior to that, the focus is on ‘autocracy’ – ie a certain form of monarchy”

Well, d’uh! Of course it would be the samoderzhaviye – the “default” option for monarchy and monarchism in Russia. Suggesting some other form would immediately disqualified the person from the ranks of the true conservatives.

“But even after the revolution, monarchism is subdued”

Again – which Revolution? We had a few of them. I surmise (probably, incorrectly) that you are skimming over the reasons as to why the mainstream, state sanctioned conservatism in the form of the monarchism took a blow in, saaaaaaay, January 1905, and even creation of the political parties expounding various versions of monarchism (like reactionary, nationalist or vernopoddanichesky no matter what the current state policy is) did not save the monarchy in February 1917.

“As I explain in my book, among emigres, the ruling doctrine was the Whites’ idea of non-predetermination.”

…For which baron Wrangel trash-talked them, being one of the open monarchists in the White Movement. But this skips description of the political theatre of the Whites-held territories, where people as diverse as Shulgin, Purishkevitch and [gasp] Savinkov found a refuge and a rostrum for their ideas.

“…But for these word clouds, I threw them all together.”

I knew that! 🙂

“Re. freedom, generally speaking we’re speaking svoboda – e.g. svobodnoe slovo,”

Yes, but in 1861 the serfs got volya. How often did the conservatives resorted to volya instead of svoboda?

LikeLike

Chapter 7 — Creation of the Russian Civilization

In the nineteenth century most historians regarded Russia as part of Europe but it is now becoming increasingly clear that Russia is another civilization quite separate from Western Civilization.

Both of these civilizations are descended from Classical Civilization, but the connection with this predecessor was made so differently that two quite different traditions came into existence.

Russian traditions were derived from Byzantium directly; Western traditions were derived from the more moderate Classical Civilization indirectly, having passed through the Dark Ages when there was no state or government in the West.

Russian civilization was created from three sources originally:

(1) the Slav people,

(2) Viking invaders from the north, and

(3) the Byzantine tradition from the south…

…In time the ruling class of Russia became acquainted with Byzantine culture. They were dazzled by it, and sought to import it into their wilderness domains in the north. In this way they imposed on the Slav peoples many of the accessories of the Byzantine Empire, such as Orthodox Christianity, the Byzantine alphabet, the Byzantine calendar,

the used of domed ecclesiastical architecture, the name Czar (Caesar) for their ruler, and innumerable other traits.

Most important of all, they imported the Byzantine totalitarian

autocracy, under which all aspects of life, including political, economic, intellectual, and religious, were regarded as departments of government, under the control of an autocratic ruler. These beliefs were part of the Greek tradition, and were based ultimately on Greek inability to distinguish between state and society. Since society includes all human

activities, the Greeks had assumed that the state must include all human activities.

In the days of Classical Greece this all-inclusive entity was called the polis, a term which meant both society and state; in the later Roman period this all-inclusive entity was called the imperium. The only difference was that the polis was sometimes (as in Pericles’s Athens

about 450 B.C.) democratic, while the imperium was always a military autocracy. Both were totalitarian, so that religion and economic life were regarded as spheres of governmental activity. This totalitarian autocratic tradition was carried on to the Byzantine Empire and passed from it to the Russian state in the north and to the later Ottoman Empire in the south. In the north this Byzantine tradition combined with the

experience of the Northmen to intensify the two-class structure of Slav society.

In the new Slav (or Orthodox) Civilization this fusion, fitting together the Byzantine tradition and the Viking tradition, created Russia. From Byzantium came autocracy and the idea of the state as an absolute power and as a totalitarian power, as well as such important

applications of these principles as the idea that the state should control thought and religion, that the Church should be a branch of the government, that law is an enactment of the state, and that the ruler is semi-divine. From the Vikings came the idea that the state is a foreign importation, based on militarism and supported by booty and tribute,

that economic innovations are the function of the government, that power rather than law is the basis of social life, and that society, with its people and its property, is the private property of a foreign ruler.

These concepts of the Russian system must be emphasized because they are so foreign to our own traditions.

In the West, the Roman Empire (which continued in the East as the

Byzantine Empire) disappeared in 476 and, although many efforts were made to revive it, there was clearly a period, about goo, when there was no empire, no state, and no public authority in the West. The state disappeared, yet society continued. So also, religious and economic life continued. This clearly showed that the state and society were not the same thing, that society was the basic entity, and that the state was a crowning, but not essential, cap to the social structure. This experience had revolutionary effects. It was discovered that man can live without a state; this became the basis of Western liberalism.

It was discovered that the state, if it exists, must serve men and that it is incorrect to believe that the purpose of men is to serve the state. It was discovered that economic life, religious life, law, and private property can all exist and function effectively without a state.

From this emerged laissez-faire, separation of Church and State, rule of law, and the sanctity of private property. In Rome, in Byzantium, and in Russia, law was regarded as an enactment of a supreme power. In the West, when no supreme power existed, it was discovered that law still existed as the body of rules which govern social life. Thus law

was found by observation in the West, not enacted by autocracy as in the East.

This meant that authority was established by law and under the law in the West, while authority was established by power and above the law in the East. The West felt that the rules of economic life were found and not enacted; that individuals had rights independent of, and even opposed to, public authority; that groups could exist, as the Church existed, by right and not by privilege, and without the need to have any charter of

incorporation entitling them to exist as a group or act as a group; that groups or individuals could own property as a right and not as a privilege and that such property could not be taken by force but must be taken by established process of law.

It was emphasized in the West that the way a thing was done was more important than what was done, while in the East what was done was far more significant than the way in which it was done…

https://archive.org/stream/TragedyAndHope/TH_djvu.txt

http://www.carrollquigley.net/books.htm

LikeLike

I understand, that’s not your own words, that you are merely quoting, but:

“Russian traditions were derived from Byzantium directly; Western traditions were derived from the more moderate Classical Civilization indirectly, having passed through the Dark Ages when there was no state or government in the West.”

“More moderate Classical Civilization” – what kind of nonsense is this?

“(2) Viking invaders from the north”

Only invaders? There were no merchants, settlers, mercenaries from the North – only invaders?

“the Byzantine alphabet”

wat

“the Byzantine calenda”

WAT

“the name Czar (Caesar) for their ruler”

…ever wonder about the etymology of the term “Kaiser” for the ruler?

“Most important of all, they imported the Byzantine totalitarian

autocracy, under which all aspects of life, including political, economic, intellectual, and religious, were regarded as departments of government, under the control of an autocratic ruler”

Bullshit. The author is a peddle of the “Eternally Oppressive East” bullshit. “Totalitarian”? Really? How can a feudal society (which was Russia for the most of its history) be a “totalitarian”?

Bankotsu, why are you quoting this – because you agree with it? If yes – care to defend the BS points the author makes all over the place?

“…in the later Roman period this all-inclusive entity was called the imperium.”

No, the author is an idiot to conflate “polis” with “Imperium” .

“From Byzantium came autocracy and the idea of the state as an absolute power and as a totalitarian power, as well as such important applications of these principles as the idea that the state should control thought and religion, that the Church should be a branch of the government, that law is an enactment of the state, and that the ruler is semi-divine.”

[…]

There is so much BS in this one sentence, but I’m going to ask about only one thing – when did the Russian rulers became claiming that they were “semi-divine”?

“This clearly showed that the state and society were not the same thing, that society was the basic entity, and that the state was a crowning, but not essential, cap to the social structure”

[…]

What “society” existed in early 9th c. lands of Franks?

“It was discovered that the state, if it exists, must serve men and that it is incorrect to believe that the purpose of men is to serve the state. It was discovered that economic life, religious life, law, and private property can all exist and function effectively without a state.”

[…]

[…]

[…]

…what an idiot… who craps his crap in other people’s minds… Unfunny propacondom, in short.

LikeLike

I was surprised about your exchange with JT on literature and/as politics. But apart from your more humorous ones, the last one definitively reads a bit like mental diarrhea.

LikeLike

“But apart from your more humorous ones, the last one definitively reads a bit like mental diarrhea.”

Please, SF, tell me more. Your opinion is so valuable, articulate and precious.

LikeLike

I am sorry, once again. I am trying to learn. As someone who has only a very, very limited grasp on matters. Meaning: I would have preferred if you had asked the question why he posted it without giving a reason first. I agree with a lot you write, but find it very, very hard to dig through your references. Maybe that’s your point?

Quigley writes in a certain time and space, as you realize. Thus my question to you would be to what extend could he be a piece of the larger tradition puzzle that explains to us “nitwits” what we experience today.

That said, once again, why did Bankotsu post the chapter of book published in 1966? What do you think.?

LikeLike

“Meaning: I would have preferred if you had asked the question why he posted it without giving a reason first. I agree with a lot you write, but find it very, very hard to dig through your references. Maybe that’s your point?”

Please, first elaborate on “mental diarrhea”. Who’s having it? What do you mean by it?

LikeLike

Please, first elaborate on “mental diarrhea”. Who’s having it? What do you mean by it?

well it actually came to mind rather spontaneously as some type of helpful shortcut. Yes, it was rude, but not without sympathy. Quite the opposite really.

If you had asked, what made me choose it? That would be the harder task. Wasn’t too surprised that others, in that case native speakers, must have used it too:

https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=Mental%20Diarrhea

LikeLike

“well it actually came to mind rather spontaneously as some type of helpful shortcut. Yes, it was rude, but not without sympathy. Quite the opposite really.”

How often you are told some “rude” words as a “helpful shortcut” to describe your posting style “with sympathy”, e.g. at SST comment section (where you are now banned)?

Please – continue. You are a gift to the Net, SF.

LikeLike

e.g. at SST comment section (where you are now banned)?

“Noli turbare circulos meos!”??? …

LikeLike

“Another way of looking at it is as a ‘reactive’ ideology – i.e. it’s a reaction to whatever is happening in the time in question.”

^This. So much this, underlined part. The implications of this, IMO, should be explained further.

Before that there was no need for any kind of ideology as the justification was one for all – “We, Monarch by the Grace of God”. The fact that there arise the need for the conservative justification, that “by the Grace of God” is not enough is, indeed, a reaction to the alternative, presented by the Great French Revolution. But by its mere appearance, by the fact that there is a need for it, it signifies the beginning of the end. By being mainly “reactionary”, the Russian (or any) conservatism is like Faust, begging for the moment to stop… time after time… totally in vain.

Some time ago, you posted here a video of your small presentation and Q&A session. You admitted there, that the conservative thought in Russia remained just that – merely a thought, not an action. You also left unmentioned that a lot of the people that you are mentioning are nowadays virtually unknown in Russia, except such “memetic” figures like Dostoyevsky or Gumilev, but even if they are known, it’s not because of their conservativeness. Left unsaid was the fact, that they, being conservative reactionaries proved to be powerless losers.

The fact is, the conservatives can’t point their finger and say – “We deed this! Weep in despair, pathetic mortal!”. Because they can’t lay claim on anything done by the Russian state – they were too oddball no matter who was currently in charge (e.g. Uvarov… so many times – Uvarov). OTOH, this makes studying them a “safe” subject.

LikeLike

A trite comment: my feeling is that the vastness and inhospitable climate of the country, by themselves, were always likely to strongly influence attitudes of its citizens. To wit, I would expect that they would generally look for a strong and supportive government. (My experience of driving big distances here in Oz did not properly prepare me for the Trans Siberian.)

LikeLike

“A trite comment: my feeling is that the vastness and inhospitable climate of the country, by themselves, were always likely to strongly influence attitudes of its citizens.”

You are right about climate and geography playing a certain, even important role in the formation of the political order, because, naturally, these factors tend to influence the economic order in the first place.

Here some historical context.

It’s widely accepted in the historiography, that the North-Eastern lands of the previously united “Kievan” Rus were the birthplace of the modern Russia. Namely – the so-called “Vladimir-Suzdal” princedom. Geographically speaking it’s on the frontier, far from the seas, mostly heavily forested area – and the second biggest principality of now disunited Rus, yet one of the more sparsely populated. Contemporaries called it “Zalesskaya zemlya” (they were not fans of the Latin to call it “Transylvania” ). A literal godsend gift was the Vladimir opol’ye region of the forest-steppes. The chief task of the local potentates, therefore, was to convert this half-forested/forested land into arable land, thus ensuring the “food security” for themselves and, potentially, a surplus to be traded elsewhere (e.g. to Novgorod). Which they did under the local branch of Rurikids, descended from Yuri Dolgoruky (“The Long Arms”).

Meanwhile in the Southern/South-Western Rus the land and climate were much, much more generous and the soil much, much more bountiful. Therefore in this region of the former united Rus lived (approximation based on the archeological data) about 2/3 of the entire population of Rus. There was one problem, though – the Wild Plain region, this land-sea of the steppes, that served as home for various nomad tribes since time immemorial. These nomads, naturally, were keen on raiding, looting and pillaging plus taking slaves from their non-nomadic neighbors. After all remaining pretenses to unity of the state collapsed in 1130s, competing princes also found very useful to “invite” different tribes of Cumans to assist them in their dynastic wars, with the payment being looking the other side when their erstwhile allies would be raping and pillaging.

At the same time, in the Southern/South-Western Rus a “healthy” feudalism was developing apace. Significant fertility of the land meant that even a couple of villages could feed not only some mid-to-high tier aristocrat, but also a number of his armed retainers. Next logical step from this reality is the appearance of the existential question – “Why do I need a Prince to tell me what to do, if I can maintain a semblance of the economic autarky, while this arsehole only takes tribute and tells me to fight in his pointless wars?!”. The inheritance system of Rus also played the role in the developing of the disconnect between the landed aristocracy (aka “boyars”) and ruling dynasties. The appanage system meant constant mobility from less prestigious “throne” to more prestigious, with the “throne” of Kiev viewed the ultimate price. By 1130s the system became so clunky and FUBARed, that virtually everyone now was claiming to be cheated out of their rightful inheritance, shafted into irrelevance while seeing the armed conflict as the only way to right the wrongs. Between 1132 and 1223 the throne of Kiev changed, ah, “hands” 44 times, with the absolute anti-record belonging to Gleb Yurievich (the youngest son of Yuri Dolgoruky) who ruled for about 3 weeks. The thing was – princes changed, while the local “oligarchs” remained, developing a shop-list of grudges and demands which they thought could be right only by the force of arms.

So the ordinary people voted with their legs and migrated to someplace much more safer – to the N-E Rus. But there came the catch – these people, often having only clothes on their backs, were nominally independent low-key land owners back in South, but after relocating to the North-East they, legally speaking, were nobodies. The land, naturally, belonged to the chief feudal, in this case, to a particular bloodline of the Rurikids, who, after some initial adventuring by Yuri Dolgoruky, decided to develop their own domain, instead of fighting for the far away throne. So, yeah, sure, they were welcoming of this “caravans of migrants” – provided that they would accept the lowering of their social status, settle in the places designated to them by the prince and paying (rather significant) tribute on time. These being the Middle Ages, naturally, people accepted this kind of “state paternalism” with a sigh of relief, given possible alternatives.

The same was true about new cities founded in 12th c. by the princely decree. They were founded as, primarily, centers of the central power, as garrisons in key areas. So the local city council (“veche”) while nominally legit was less developed compared to “old” cities like, Kiev, Novgorod or Rostov the Great.

LikeLike

I used to think that advocates of the “eternal repressive East”-meme could be shut down by shouting “VELIKIJ NOVGOROD!”, much like one can shut down Panslavinists by shouting “POLAND!” (Thanks Lyttenburgh). Unfortunately it just get you blank stares.

LikeLike

no blank stares in my case. Confusion, frustration, maybe? I find Lyttenbourg’s comments helpful but really hard to dig through. They are definitively way more complex then at the point our ways crossed first.

Random pick, how close did I get to her argument by looking up her references to diverse Russian revolutions? It feels there is solid ground too for comparable references in the “Western Civilization”. Are there experts on revolutions vs the Revolution? Did she have the “revolution” post Gorbachev in mind too? Or wouldn’t she consider that a revolution?

More randomly an observation from my own ground, Europe. We seem to have two types of revolutions facing each other presently.

One question from my own frustration pool, far, far away from the topic here: Should I give the larger European Spring revolution movement more support than its nationalist counter movement? Any help you can offer? You feel the nationalist counter movement is conservative only? While progressive snowflakes’ over here should take a close look at the Arab Spring, realizing they are dreaming only?

LikeLike

Velikij Novgorod should stop such things because it happened to be the territorially largest republic in Europe for a pretty considerable timespan.

Or the fact that there is actually plenty in Russian culture that is quite egalitarian

LikeLike

” much like one can shut down Panslavinists by shouting “POLAND!” (Thanks Lyttenburgh)”

Panslavism in one meme.

LikeLike

The yawning contrast between Western assessments of Dugin’s (apparently including, to some extent, Robinson’s book) influence and his completely marginal status in Russia, never fails to amuse. For instance, in the past few years, the cultural influence of something like Sputnik & Pogrom would have exceeded Dugin’s by at least an order of magnitude if not two.

LikeLike