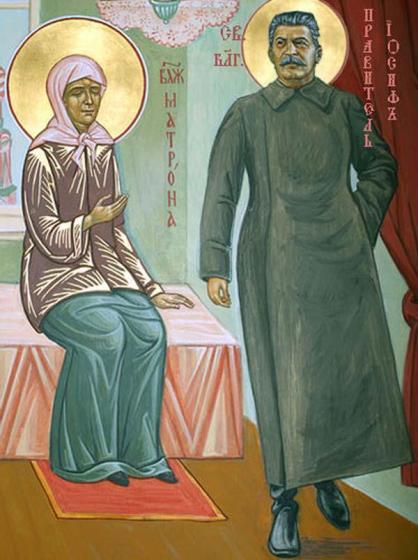

In the 1930s, the Young Russians movement of Alexander Kazem-Bek attempted to rally Russian emigres around the slogan ‘For Tsar and Soviets’. It didn’t catch on, but if Kazem-Bek were alive today, he would find his idea doing rather better. As a historian, one of the things I have found most striking about Russia in the past decade is the way that its people manage to mix together utterly contradictory symbols and beliefs, such as Tsar and Soviets. Extreme examples include a scandalous icon which briefly appeared in a St Petersburg church in 2008 and which depicted a meeting between Stalin and the blind holy woman Saint Matrona of Moscow in 1941, and another Stalin icon which was displayed in June 2015 at Prokhorovka, the site of the largest tank battle of World War II. Other less outrageous mixings of the Soviet and the Orthodox, or the Soviet and the Imperial, abound.

A lot of Russians seem not to notice the obvious inherent contradictions in mixing these things together. Rather, they appear to synthesize them in a way which somehow makes sense to them. I found it interesting, therefore, to observe Russia’s Foreign Minister, Sergei Lavrov, doing the same thing in an article he wrote last week for the journal Russia in Global Affairs.

Lavrov starts his article by saying that he perceives the debate about Russia’s role in the world ‘as an echo of the eternal dispute between pro-Western liberals and the advocates of Russia’s unique path.’ The key line in the article comes about half way through when Lavrov writes of ‘the importance of the synthesis of all the positive traditions and historical experience as the basis for making dynamic advances and upholding the rightful role of our country as a leading centre of the modern world.’ An attempt to produce such a synthesis is the core of the essay.

Lavrov uses history to make a strong case that Russia is a European country. Kievan Rus, he says, was ‘a full member of the European community. … Rus was part of the European context.’ Later, ‘the rapidly developing Moscow state naturally played an increasing role in European affairs’. ‘Not a single European issue can be resolved without Russia’s opinion’, writes Lavrov, adding that ‘any attempts to unite Europe without Russia and against it have inevitably led to grim tragedies.’ Even now, Russia remains open to ‘the dream of a common European home.’

And yet, Lavrov remarks, the ‘Russian people possessed a cultural matrix of their own and an original type of spirituality and never merged with the West.’ The Mongolian invasion created ‘a new Russian ethnos’, and Alexander Nevsky was right to ally with the Mongols, ‘who were tolerant of Christianity’, and to fight the West which wished to ‘put Russian lands under full control and to deprive Russians of their identity.’ Having earlier remarked that, Russia, ‘is essentially a part of European civilisation’, Lavrov later implies that it is a civilisation of its own by saying that, ‘long-term success can only be achieved on the basis of movement to the partnership of civilisations based on respectful interaction of diverse cultures and religions.’ Lavrov thus seems to want to have it both ways – Russia is European and is unique.

In his final paragraph, Lavrov finds a way out of this apparent contradiction by citing Ivan Ilyin, who wrote that ‘the greatness of a country is not determined by the size of its territory or the number of its inhabitants, but by the capacity of its people and its government to take on the burden of great world problems and to deal with these problems in a creative manner. A great power is the one, which asserting its existence and interest … introduces a creative and meaningful legal idea to the entire assembly of nations.’ This is a classic Slavophile position, derived from German Romanticism: nations contribute to humanity by developing what is best about their own unique identity. In this way, Russia best serves Europe and European civilization not by copying Europe but by being true to its own Russian self.

If that were all that Lavrov had to say, one could conclude that he had indeed managed to produce a successful synthesis. However, Ilyin isn’t the only source he refers to. Lavrov also makes mention of poet Alexander Pushkin, philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev, ethnographer Lev Gumilev, and American politician Henry Kissinger. Elsewhere, Lavrov’s talk of ‘cultural and civilizational diversity’ carries hints of Samuel Huntington’s book Clash of Civilizations and of 19th century conservative philosopher Konstantin Leontiev. These are all strange bedfellows. The Eurasianist Gumilev and the anti-Eurasianist Ilyin, for instance, don’t fit together very easily.

Nor does Ilyin fit well with the comments Lavrov makes about the Soviet Union. The revolution of 1917 and subsequent civil war ‘were a terrible tragedy’, he says, but ‘it was a major event which impacted world history’, and it helped spread ideas of social reform into Western Europe, if only ‘to cut the ground from under the feet of the left-wing political forces.’ The influence of socialist ideas had a positive effect on the world, Lavrov maintains, and ‘the role which the Soviet Union played in decolonisation … is undeniable’. One can argue about the accuracy of these statements, but to put them side by side with a quote from Ilyin, who denied any good in Soviet communism, is very much like painting the icon of Stalin and Matrona.

Lavrov’s article makes some important points. I fully endorse his suggestions that isolating Russia does not serve Europe well and that ‘a reliable solution to the problems of the modern world can only be achieved through serious and honest cooperation between the leading states.’ But the only way one can make Lavrov’s synthesis work is to be highly selective in one’s choices of historical examples and philosophical quotations – mention the bits of Soviet history you think are positive, and ignore all the rest; and cite those phrases of Ilyin which you like, and forget the other stuff he wrote which you find uncomfortable. As long as you don’t stop to think too deeply about it, it works. But once you do start thinking, it’s not desperately convincing. Philosophically, the article is a bit of a hodge-podge.

Very interesting analysis. The juxtaposition of Gumilev and Ilyin seemed a little odd to me as well.

LikeLike

Great analysis, as usual – thanks.

However, I would have to disagree with the statement: “… the only way one can make Lavrov’s synthesis work is to be highly selective in one’s choices of historical examples and philosophical quotations – mention the bits of Soviet history you think are positive, and ignore all the rest.”

The trouble with this statement is the assumption it relies on – that any synthesis can be made to work using any other approach.

In reality, no nontrivial intellectual argument can be constructed by any means other than “mentioning all the source materials that support it and ignoring the rest”. Furthermore, this selectivity is not just an unfortunate feature of totalising discourses in the west (e.g. those surrounding so-called “human rights”), but their fundamental attribute. The stubbornly irrational insistence that this is not so is one of the primary factors leading to their present incoherence.

Contemporary Russian thinkers, including the excellent Dugin, are similarly constrained, as you rightly point out in your critique of Lavrov’s “Russia’s Foreign Policy: Historical Background”.

However, I don’t think you would find anyone disagreeing with this – least of all the authors themselves. Let’s take Dugin’s “Fourth Political Theory”, with which I assume you are already familiar.

“The second and third political theories [i.e. Fascism and Marxism] are unacceptable as starting points for resisting liberalism, particularly because of the way in which they understood themselves, what they appealed to, and how they operated. They positioned themselves as contenders for the expression of the soul of modernity and failed in that endeavour. Yet, nothing stops us from rethinking the very fact of their failure as something positive, and recasting their vices as virtues.”

The reason why contemporary Russian discourses, including the arguments contained in Lavrov’s “Russia’s Foreign Policy: Historical Background”, are more coherent than their western, liberal counterparts, is because they do not insist on the idea that just because you quote Ilyin or Gumilyov you must therefore assume that all their arguments were “correct”, including as applying to the rather different context in which one finds oneself today. This, on the very face of it, would be absurd and it’s rather strange that “we” do not forthrightly admit it.

The totalising discourses of liberalism, including those referring to so-called “human rights”, are under attack. Indeed, it may fairly be assumed that they are currently on their last stand. However, their enemy is not “Eurasianism” or any other strand of contemporary Russian discourse, and it would be useless for them to attempt to defend themselves against this line of attack.

Rather, the totalising discourses of liberalism are facing imminent collapse due to their own intellectual incoherence. “We” don’t need Sergey Lavrov, Alexandr Dugin, Vladimir Ilyin or Nikolai Gumilyov to tell “us” that! Even Donald Trump and his motley supporters understand this! A child can understand it!

Lavrov’s main point, as I understand it, is that Russia is once again called upon to play its historical role as “ark” of European culture. I place all my confidence in Russia’s present ability to perform this role, since the alternatives don’t bear thinking about. All the rest is just intellectual game theory (and there’s nothing wrong with that, after all, is there?).

LikeLike

Yes, I also enjoy the excellent Dugin entertainment productions. Especially his concept of “conservative science”, which sounds just like “marxist science” leading straight to a new lysenkoizm. And as for your hopes for Russia to become “ark” of European culture – as for now it’s closer to being an orc indeed.

LikeLike

I’m glad you are able to enjoy the irony the Dugin applies to the ironising neoliberal discourses. That for me is one of the real joys of straddling the Russian- and English-speaking worlds, a joy I imagine must be sadly lacking in the lives of the genuinely monolingual and monocultural.

LikeLike

I don’t “hope” that Russia “will become” an ark; rather, I assert that it already is one. Or, rather, I agree with Lavrov’s (and other writers’) suggestions that it has played this role many times in the past and can be expected to play this role again in the future. Obviously whether or not this turns out to be the case in our own time remains to be seen. We live in hope.

LikeLike

Oh, so it’s called irony these days. This Dugin’s speech on travels must be also an irony as well, silly me.

LikeLike

I love the tourism piece. The only one I like better is the one about the social media…

LikeLike

“mention the bits of Soviet history you think are positive, and ignore all the rest; and cite those phrases of Ilyin which you like, and forget the other stuff he wrote which you find uncomfortable. As long as you don’t stop to think too deeply about it, it works. But once you do start thinking, it’s not desperately convincing. Philosophically, the article is a bit of a hodge-podge.”

So you are suggesting to do what exactly? Concenctrate only on “bad stuff” – in a country like Russia? Proclaim one time period superior to all others? Don’t even try to synthethize anything?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lavrov wasn’t quoting anything from Ivan Ilyin’s philosophy, he was only quoting something Ilyin said about how the greatness of countries is judged on how well their governments and people deal with universal problems and how creative their responses are. That might well be a universal observation that any philosopher, regardless of their political orientation or bias, could make. In the context that Lavrov was quoting Ilyin, he wasn’t cherry-picking any particular beliefs or ideas to bolster his arguments in a shallow way.

Is Lavrov not allowed to quote selectively, choosing quotations that he thinks might express a viewpoint more succinctly than he can or which agrees with his?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Besides, quoting other thinkers is a way of placing your own argument into a particular context – in this case, the history of Russian ideas, of which Ivan Ilyin (excuse the typo in my previous comment) is an important near-contemporary figure. Not to mention Nikilay Gumilyov! I have the feeling only refrained from citing Dugin due to the successes on the part of “liberal intelligentsia” in branding the contemporary philosopher as a dangerous liability.

LikeLike

Seem fine to me; Lavrov, that is. “The eternal dispute between pro-Western liberals and the advocates of Russia’s unique path” is the synthesis. Unity of opposites; the road up and the road down are the same thing. Sure, Stalin and Matrona, why not? Read some Dostoyevsky, will ya?

Moreover, I suspect all cultures are sort of like this, and all human beings. Maybe not always as pronounced, but nevertheless.

LikeLike

My dear, there’s no “dispute between Western liberals and Russian unique path”. It’s very simple inconsistency between having a theoretical law written on paper and practical prosecutors selling pardons for 30k roubel in real life.

LikeLike

Why, bribery is very much a European/capitalist phenomenon, is it not? What is your point?

LikeLike

No, according to Corruption Perception Index it is definitely not associated with liberal, capitalist democracies. There were bribes in Soviet Union. And there now are bribes in Venezuela. In both cases they originate primarily from the shortage economy, which is a typical feature of Marxian socialism.

LikeLike

Yes, bribery is a capitalist phenomenon. I believe I already commented on the ‘Corruption Perception’ thing here somewhere. I forgot the number: is it 100,000 lobbyists in Washington? Bribing politicians to the extent of $1 billion/year? or is it $10 billion? $100? I forgot.

Also, have you heard the story about subprime mortgages a few years ago? Rating agencies? Goldman Sachs and other Wall Street institutions? What was that – about $10 trillion worth of corruption? And you’re outraged about 300 rubles? Oh dear…

LikeLike

For all of thee, dounting Thomases, who don’t even consider equating “bribery” and the “western liberal democracy” – behold!

LikeLike

You are comparing apples and oranges. Lobbying and white-collar crime is one thing, and happens in both Russia and Western states, everyday bribery is a phenomenon unique for Russia and other countries painted red in CPI. I don’t know where you live, but your lack of knowledge from Eastern European reality sounds like you never had to pay a bribe at doctors, court, police or any other public office, which sounds just like the Western world. And the price you mentioned – 300 roubel was something you might pay to a policeman 10 years ago for crossing the street at red light. The price for pardon mentioned in the article was 30’000 roubel.

LikeLike

I live in central Europe now. ‘Gifts’ to doctors and nurses is very common here. In most of the rich countries it’s much worse, only it’s all legalized, via private insurance and other mechanisms. One big problem I’m aware of, at least in the US, is pharmaceutical companies bribing doctors to prescribe their pills. All perfectly legal, of course.

So, the difference is, in the West bribery is legal and on the industrial scale, whereas in Russia it’s still amateurish and illegal. It’ll change, of course. But it takes time for the political system to sort things out.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“I don’t know where you live, but your lack of knowledge from Eastern European reality sounds like you never had to pay a bribe at doctors, court, police or any other public office, which sounds just like the Western world. And the price you mentioned – 300 roubel was something you might pay to a policeman 10 years ago for crossing the street at red light. The price for pardon mentioned in the article was 30’000 roubel.”

I live in Russia. Moscow and region. And, yes – I never have paid a bribe in my entire life. Shocking, right?

That fine that I got for a jaywalking was issued to me in January, 2009. 200 rubles. Not a birbe. A fine.

As for zhe and zhe having to pay bribes – maybe zhe are engaged in something that demands that? Or zhe look like a sucker

Also – did zhe even wathced the film? It talks not about just “lobbying”.

LikeLike

Unfortunately, it is not a “hodge-podge” but a skillfully prepared dish, i.e., a “one-piece of meat” both for Russians and for foreigners. It is impossible to say more not spoiling the sense of it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This hodge-podge is simply result of approaching the history and philosophy from a purely instrumental point of view. Lavrov is not reaching to history to learn something and avoid past mistakes, he’s reaching there to support the nowadays policy. The whole geopolitical concept for example has replaced what dialectical materialism was in USSR – a tool for deconstruction of any logical counterarguments and observations.

As for the Bolshevik revolution spreading “social ideas” – it did precisely the opposite. Social ideas were being spread since 19th century, with no one else but Adam Smith proposing public education half a century before Marx, with first labor laws introduced in Europe in mid-19th century. What the revolution helped to spread was the idea that you can achieve equality and wealth by physical extermination of the bourgeoisie class, however loosely defined. An idea that many peers have like Kautsky and Russell have opposed at that time, precisely realizing that it will result in nothing else than USSR eventually became.

Also Lavrov’s proposal in the final words is rather ridiculous as I can’t imagine anything further from “a serious and honest cooperation” than annexation of piece neighbor country’s territory, a large scale covert operation in another part of it, downing a passenger plane – and denying that they have anything to do with that. I wonder if he’s so detached from reality or just trolling?

LikeLike

“As for the Bolshevik revolution spreading “social ideas” – it did precisely the opposite. Social ideas were being spread since 19th century, with no one else but Adam Smith proposing public education half a century before Marx, with first labor laws introduced in Europe in mid-19th century. ”

Pfft! Why not go even furhter back in time then, userperson Cortez, and not claim, that it was in 5 c. BC when a progressive, democratic and liberal playwriter Aristophanes porposing equal voting rights for men and women? Granted, between “proposing” and actual “implementation” it took some time – a mere moments (from geological standpoint).

While the USSR was the first country in the world to successfully implement following social rights:

– Right on 8-hour working day.

– Right on yearly paid vacation.

– It was impossible to fire a worker by management/owner’s decision without support from local union or party organisation

– Right to work. All graduates of professional colleges were guaranteed an employment on their speciality which would also come with an apartment,

– Right on free education – for everyone, on all levels.

– Right on free use of children pre-school facilities, like kindergardens.

– Right on universal free healtcare.

– Right on free use of sanatoriums and resorts.

– Right on free housing (for working persons).

– Right on free use of the public transportation for a certain categories of people (veterans, children, elderly).

Not “proposed”. Implemented.

” than annexation of piece neighbor country’s territory”

I always forget – zhe are Russian or Ukrainian? Because it wasn’t an annexation – it was re-union.

“downing a passenger plane – and denying that they have anything to do with that”

Now, zhe are accusing Russia?

LikeLiked by 1 person

“it was re-union”

Yes, that’s precisely what I meant. Annex – make a fake referendum – and then call it something like “a friendly re-union”. This works internally, but apparently the rest of the world doesn’t consider that to be anywhere close to the “honest and friendly cooperation” as hallucinated by Lavrov.

“Not “proposed”. Implemented. ”

Yes, these were perfectly implemented in the Consitution of the USSR. In a row with freedom of speech, religion and other liberties for which Soviet Union was famous worldwide. Do you know what happened in Novocherkassk in 1962 for example?

LikeLike

“Yes, that’s precisely what I meant. Annex – make a fake referendum – and then call it something like “a friendly re-union”.”

I’m sorry, do ou doubt that the residents of Crimea indeed wanted to be reunited with their brethren* in therest of Russia? Can you prove, that they were coerced in any way to vote against their will? Like – truly prove?

My dear userperson Cortez – if you want to know – if you care to know – Crimea’s re-union with Russia was in fact a Triumph of Liberalism. You should be glad and cherring.

For the rest of you, I’d like to provide a statistical data provided here (with links to sources and all that jazz). An artilce liked by – burst my eyes if its not true! – Professor Poul Robinson himself – a proud owner and propertitor of this respectable establishment.

________

* Ohhhhh! I can practically see how you are BURNED by this simple turn of phrase – “brethren”!

“Yes, these were perfectly implemented in the Consitution of the USSR. In a row with freedom of speech, religion and other liberties for which Soviet Union was famous worldwide. Do you know what happened in Novocherkassk in 1962 for example?”

This is just an attempt of pathetic “whataboutism”. I was talking about social rights. Have you ever read the Soviet Constitiuion, say, “Stalin’s” of 1936? There is nota word about “freedom of religion” – only that the church is separated from the state and has no place interfering in the affairs of the society.

I’m abundantly aware of what has happened in Novocherkassk in 1962 – get over with your “whatabourism”, already – a suppression carried out by the order of anti-Stalinist Khruschev, one of the darlings of the West and our local liberasts.

And, surely, in 1962 the Blessed Valinor of the West was also well known for its freedom of speech for various minorities and “unbecming” politicians – right?

LikeLike

I’m curious if it’s ever permissible to quote “all men are created equal” without “I advance it therefore as a suspicion only, that the blacks, whether originally a distinct race, or made distinct by time and circumstances, are inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind.” (from Notes on the State of Virginia)

LikeLike

Good one. And right on the money in case of this post.

LikeLike

If the point you are making is that others, e.g. Americans, are also selective in their historical references, then of course you are right. But as a general rule, people aim for consistency in their selectivity. So, if you are trying to advance a view of American history as a progress towards liberty and democracy, you will focus on the bits which reinforce that story, and not add in bits which show something opposite. In Lavrov, we see something different – highly opposed historical and philosophical narratives flung together. It is as John Kerry decided to write a piece in which he cited Martin Luther King and then followed it up with a quotation from Jefferson Davis.

LikeLike

“But as a general rule, people aim for consistency in their selectivity.”

What Lavrov does here is tacking little steps in formulating new Russian idology based on patriotism. And this means – not flinging tons of shit at your history, accepting it as it is, learing (quitely) lessons from it while extolling the positive examples for all to see and admire.

Hardly aything new or unique.

“It is as John Kerry decided to write a piece in which he cited Martin Luther King and then followed it up with a quotation from Jefferson Davis”

You can perfectly well write a thesis on “American history as a progress towards liberty and democracy” ™ though, using chosen quotes from the Founding Fathers (but not about the race… or gays…), both Abraham Lincoln and his confederate opponents (we don’t want to drive a wedge here, right?) and so on and so forth.

History out of Ivory Towers of academia is used exactly for that.

LikeLike

It is one narrative. Either as Russian history or as Russian thought. You just look from wrong angle.

Same story with icons. Stalin actually is not so strange a historical figure to paint there, but Lenin would be. Yet I’m pretty sure you can find icon with Lenin. Why is that? Because people are not really interested in their relationships with church or in church in itself. To put it really simply they merge their faith in higher benevolent power with leaders they remember as benevolent and whom they consider representatives of higher power on Earth.

Lavrov piece was written to underline importance of Russian role in world affairs and as such it could be argued on many points. But those points are not “conflicting philosophies” as they do not as much conflict in history or even in modern day Russian perception as they compliment each other.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, too bad. Citing Martin Luther King followed by Jefferson Davis would make a far more interesting and nuanced narrative. Dialectical thinking vs. primitive dualism of glamorization and denunciation, so typical for the liberal west (in the mainstream, at least) these days? I know what I prefer…

LikeLike

In civic life in the American South, celebrating both MLK and the Confederacy has been the norm for over a generation. In several states of the old Confederacy, both MLK day and Confederate Memorial Day are government holidays and– until very, very recently– it was expected that politicians would give lip service to both. Such contradictions are to be expected when objectively awful historical realities form a core part of people’s identity.

LikeLike

If I were to write a narrative of American history as a progress towards liberty and democracy, to be completely honest I would need to show how that that progress wasn’t necessarily inevitable and that along the way the American nation faced many choices, some of which could have led the US in retrograde directions. I would have to demonstrate that there were periods in which American society persecuted individuals or communities for daring to exercise their First Amendment rights or denied people their Sixth Amendment rights. I would need to show that progress towards liberty and democracy is a path that people cannot take for granted and that it is something Americans continually have to fight for. In such a context, it would be entirely appropriate to cite people like Martin Luther King in some parts of the narrative and at other parts of the narrative to cite people like Senator Joseph McCarthy.

To advance a view of American history as progress towards liberty and democracy, and simply select those examples and quotations that support that “progress” as something automatic and predetermined would not only result in a shallow piece resembling propaganda, it would also be highly insulting to those Americans who fought for that progress and sacrificed their lives for it.

LikeLike

I’m sort of in the middle on this one. I agree that there’s no problem with Lavrov borrowing a quote from whoever he likes, without worrying about whether he agrees with anything else they might have said. Quoting someone doesn’t necessarily imply that you have any sympathy for their thought as a whole, much less with all the specific details of their thought. However, there are some places where Lavrov goes beyond merely quoting, and (I think) gets himself into a bit of trouble.

The best example of this is the two sections where Lavrov praises Russia’s role in enforcing the Concert of Europe system after the Napoleonic Wars, then later goes on to praise the supposed positive role of the Soviet Union in European affairs. The problem is that, in at least the early Soviet era, the Soviet Union was acting on exactly 180 degrees different principles than in the Concert of Europe era. This contradiction isn’t so easy to dismiss as a simple quote. Lavrov talks about both eras in positive terms, so intellectually he “takes responsibility” for them, with all the contradictions that implies. You can praise your country, if you like, for being the “gendarme of Europe”, propping up the most reactionary monarchies of the continent, or for being the revolutionary vanguard, but it’s pretty hard to do both at once.

The problem with appealing to some idea of “synthesis” to resolve the difficulty is that any successful synthesis has to have a coherent principle. Actually, the Ilyin quote is a good way of stating it

‘the greatness of a country is not determined by the size of its territory or the number of its inhabitants, but by the capacity of its people and its government to take on the burden of great world problems and to deal with these problems in a creative manner. A great power is the one, which asserting its existence and interest … introduces a creative and meaningful legal idea to the entire assembly of nations.’

The question is, what “meaningful legal idea” can possibly lead to praising both the gendarme of Europe and the Soviet regime? Looking for such a central idea in Lavrov’s article, the only principle I can find is the worship of Russian power as such. It seems that, as long as Russia is able to compel other countries to pay attention to its views and to make its influence felt across Europe and Asia, Lavrov is happy, whatever the principle that Russia is following in exerting that influence. This is a deeply unprincipled stance.

That said, I don’t mean to judge Lavrov too harshly. I think that, after all the fuss about Putin’s comments on Lenin, he was probably trying not to rock the boat on that side too much. When you keep in mind that this article was written by a politician, it’s not bad, and does make some good points about Russia’s liminal status in Europe, which means that it can never be treated as if it’s completely “out”. But when considered as an attempt at an expression of a general theory of Russian foreign relations, it’s more than a little thin. If Russia continues on its current path (which, for lack of a better word, I’m going to call “Putinist”), I think it’s going to eventually going to have to be willing to definitively throw Lenin and Stalin under the bus. Russia’s main ambition now seems to be to act as a conservative status quo power, resisting the attempts of America and other Western countries to selectively ignore international law, but without any revolution of its own to export. On such a basis, the Khrushchev and Brezhnev eras are at least partially salvageable, and perhaps the post-WW2 Stalin era, but Soviet history before that is hopeless.

LikeLike

“Lavrov praises Russia’s role in enforcing the Concert of Europe system after the Napoleonic Wars, then later goes on to praise the supposed positive role of the Soviet Union in European affairs. The problem is that, in at least the early Soviet era, the Soviet Union was acting on exactly 180 degrees different principles than in the Concert of Europe era. ”

Did you even read the article? Where exactly Lavrov “praises” pre-war USSR role in the European affairs? He clearly talks about post 1945 period, not the previous one when nearly all “progressive humanity” was trying to eradicate “plague of bolshevism” – preferable, with the country itself.

“The question is, what “meaningful legal idea” can possibly lead to praising both the gendarme of Europe and the Soviet regime? ”

Patriotism. Is it so alien cocept to you?

“It seems that, as long as Russia is able to compel other countries to pay attention to its views and to make its influence felt across Europe and Asia, Lavrov is happy, whatever the principle that Russia is following in exerting that influence. This is a deeply unprincipled stance.”

You’d rather prefer Russia to be compelled by other countries and pay attention to their views, instead of being a major power? Sorry, not can do. “Bears are bad at impersonating the hamsters” (c)

“If Russia continues on its current path (which, for lack of a better word, I’m going to call “Putinist”), I think it’s going to eventually going to have to be willing to definitively throw Lenin and Stalin under the bus. ”

No. Rather the opposite – Russia can’t do anything but embrace Lenin and Stalin’s legacy in full. Because to do othervise is to pander bother to the so-called liberals and ultra-nationalists like the ones in the Ukraine. I sense wishful thinking and projecting on your part, Mr. Ward.

LikeLike

“Did you even read the article? Where exactly Lavrov “praises” pre-war USSR role in the European affairs? He clearly talks about post 1945 period, not the previous one when nearly all “progressive humanity” was trying to eradicate “plague of bolshevism” – preferable, with the country itself.”

It’s true that Lavrov doesn’t dwell so much on the pre-WW2 era, but he doesn’t ignore it, or suggest that it’s an exception to his general trend of praising all the eras of Russian diplomatic history. He goes out of his way to say that it’s important to take the “positive aspects” from “all its (Russia’s) periods without exception.” This is hardly consistent with repudiating the early Soviet period. Lavrov also comments, “Without a doubt, the Revolution of 1917 and the ensuing Civil War were a terrible tragedy for our nation. However, all other revolutions were tragic as well. This does not prevent our French colleagues from extolling their upheaval…” Presumably, this means that Lavrov means to “extol” not only the later periods of Soviet history, when the Soviet Union had become anything but a revolutionary state, but also the time of its revolutionary birth, just as the French (or at least the “mainstream” ones) tend to hold a fairly high view of their early revolutionary period.

“Patriotism. Is it so alien cocept to you?”

Patriotism of that unprincipled kind isn’t an “idea” at all. It’s just a prejudice. It certainly isn’t the sort of “meaningful legal idea” that Ilyin mentioned. It’s just what I described, the mere worship of national power as such.

“You’d rather prefer Russia to be compelled by other countries and pay attention to their views, instead of being a major power? Sorry, not can do. “Bears are bad at impersonating the hamsters” (c)”

This is the “either/or” fallacy. Of course, in reality, there are many more than these two options. You might as well accuse me of saying the sky is brown because I say it’s not green.

“No. Rather the opposite – Russia can’t do anything but embrace Lenin and Stalin’s legacy in full. Because to do othervise is to pander bother to the so-called liberals and ultra-nationalists like the ones in the Ukraine. I sense wishful thinking and projecting on your part, Mr. Ward.”

My comment can’t be “wishful thinking”, because I didn’t say anything about what Russia is going to do, just about what it’s going to have to do to be rationally consistent while continuing on its current path. That in no way implies that Russia won’t either a) change its path or b) just keep on ignoring its present contradictions. Those are empirical questions, whereas my point was a logical one.

As to whether definitively breaking with the history of the Soviet Union will give “aid and comfort” to phony liberals and ethnic nationalists, it might or it might not. In any case, I don’t think it’s a good way to make decisions to worry too much about the danger of people agreeing with you for the wrong reasons. That’s their problem. Anyway, toeing the communist line has hardly been much protection against destructive nationalism in the past. The red/brown coalition of the 1990s was sufficient proof of that, and things haven’t really changed much since then. As the social scientist Marlene Laruelle commented, “Since the 1990s, “internationalist” communists have been practically non-existent in Russia…Public assertions of so-called communist convictions have thus become almost a sure sign of “nationalism”.

LikeLike

Criticising Lavrov’s article on philosophical grounds is a pointless exercise. Lavrov is not a philosopher, he is a diplomat and foreign minister. The Russian Federation is not an idea but, like all states, a geopolitical reality. Geopolitical realities are not predicated on philosophical consistency, but on history and geography. Muscovy, the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation, although operating on the basis of different ideas, all faced more or less the same geopolitical reality, that is, being state entities centred on and dominating the great European plain. These state entities were/are still part of Europe in that they were part of the same cultural/intellectual tradition (Christianity/Empire/Modernising Authoritarianism/Socialism) and also in that their interests were intimately tied to European developments in a way that those of China or even the Ottoman Empire and now Turkey have never been. At the same time, their nature as gigantic continental countries made them quite different to the more compact states of Europe who all have to share what is essentially a largeish peninsula.

This is not then a philosophical confusion but a very specific geopolitical condition. As long as Russia remains Russia, the intellectual background of its politics will seem hodge-podgy. It was only as the Soviet Union, because of its universal ideology, that the geopolitical entity that is ‘Russia’ could become more consistent in its outlook.

LikeLike

Lavrov chose to make what is in fact a philosophical argument about Russia`s place in the world, and so it is perfectly fair to criticise him on philosophical grounds.

As for the point Ryan made about it not mattering whom people cite, I disagree. If you are looking for a suitable quotation to give your article or speech some sort of intellectual kudos, you can get it from all sorts of people. The fact that you choose to get it from one person not another is meaningful. If nothing else it shows that you consider that associating yourself with that person is intellectually and politically respectable. Which is why Russian leaders don`t quote communists like Lenin any more. It`s also interesting that they don`t cite liberal thinkers of the past like Miliukov. Miliukov isn`t part of the zeitgeist; you don`t want to attach his name to yours. But Gumilev is, and you do. That tells us something.

LikeLike

This is a fair point. But maybe there’s also something else: for a piece like this you don’t want to quote anyone too controversial (Lenin) or too obscure (Miliukov). Ilyin and Gumilev sound about right: both intellectuals, neither one a politician…

LikeLike

I am not sure that I agree Lavrov’s article is philosophical. Lavrov is making a statement on the guiding principles of Russian foreign policy based on a specific reading of history. He is thus arguing from history, rather than on the basis of any clearly stated idea. This may in itself be predicated on a philosophical position on what states are (it would roughly coincide with realist positions in International Relations theory) but the argument made (‘Russia is both European and special’) is not in itself strictly speaking philosophical. Lavrov quotes Ilyin approvingly on his position that greatness is not size but influence but does not seek to develop a theory of Russian FP on the basis of Ilyin’s thought and cannot thus be meaningfully criticised for citing other thinkers who may be seen as antithetical to him. In fact, one can agree with the idea that greatness=influence and be a Marxist-Leninist, Muslim fundamentalist, Irish Republican, American Liberal or Rastafarian.

But the point here is that Ilyin is not used here because his thought is the underlying principle of Russian fp. It is used, as you seem to indicate above, more as a sign to signify a particular Russian tradition, a tradition that includes both Ilyin and Gumilev, but not Lenin or Miliukov. I think Lyttenburgh’s description of this as a statement of Russian patriotism is fairly accurate. Patriotism does not have to be *philosophically* consistent. Its consistency is provided by its geo-political referent.

LikeLike

Paul, it’s your opinion that Lavrov makes a philosophical argument but from the comments that your post has attracted, I see several responders including myself don’t agree that he has. We see him making an argument about Russia’s place in the world based on a Russian viewpoint of history – because he was brought up and educated as a Russian, and therefore perhaps he was exposed mainly to Russian sources and points of view, one of whom happens to be Ivan Ilyin who happened to be a philosopher who was critical of the Soviet system and the values it was based on, and who lived and taught in Nazi Germany for a time.

In a previous comment, I mentioned both Martin Luther King and the former US senator Joseph McCarthy in a hypothetical context of writing a narrative about American history as progress towards greater freedom and democracy. Does my mention of McCarthy suggest that I agree with what he did to stifle Americans’ First Amendment rights? I suggest it does not. In like manner, Lavrov’s quotation of Ilyin does not necessarily suggest that Lavrov is a follower of Ilyin’s philosophy or a believe in Ilyin’s worldview.

Sure, Lavrov’s education and reading may have been narrowly focused and if he relies on something Ilyin said about something that might be considered universal and free of ideology – that what makes a nation great as opposed to what makes a nation ordinary is how nations deal with problems and crises and what solutions they come up with – that is because perhaps Ilyin, so far as we know, is the only sage person Lavrov knows of to have made that observation.

LikeLike